Despite it being a week to celebrate the biggest stars in the league and home runs, it’s time to have the tough conversation about the MLB’s CBA. We released an article earlier in the year about the CBA but I thought it needed a huge overhaul. Despite the MLB’s CBA not expiring in over 500 days, more specifically on December 1st 2026 at 11:59 ET, it’s never to early to talk about the potential issues that will be looming over the negotiations. Let’s have the tough conversation about the potential lockout looming over the MLB’s, fans, players, agents and the MLBPA’s heads currently.

But before we get to that point, let’s talk about the history of the MLB CBA and its effect on the league and its biggest changes throughout the years.

First off in 1972, the first players’ strike in Major League Baseball’s history which lasted 13 days, spanning from April 1st to April 13th, 1972. The owners agreed to add salary arbitration to the CBA, as well as adding a 500,000$ increase in pension fund payments. In total the MLB missed a total of 86 games and were not rescheduled due to the league refusing to pay the players for the time they were on strike.

Interesting Note: As I was studying up on the 1972 season, due to those games not being rescheduled. The Tigers played one more game than the Red Sox.

That season , the Tigers finished with a record of 86-70, winning the American League East. While the Red Sox finished with a record of 85-70, finishing half a game behind of the AL East, Detroit clinched the division after beating the Red Sox at home, 3-1.

In 1973, the Major League Baseball lockout took place during the time of February 8th to February 25th. This lockout didn’t affect any games, but it did affect the early period of spring training when pitchers and catchers report. The lockout was initiated by MLB’s team owners, who mainly wanted an agreement with the MLBPA on the use of arbitration in settling salary disputes.

The resolution was reached after both sides agreed to a three-year agreement between owners and the MLBPA, under which it’s players with two years of consecutive MLB service (also three-years of non-consecutive service) could use the arbitration services.

The 1976 lockout was arguably the biggest at the time during these CBA discussions. It started the abolishment of the reserve clause. The reserve clause was part of the player’s contract which meant that once players signed their contracts, players could at any time, be reassigned, traded, sold or released.

The only leverage player had at the time was to hold out and refuse to play any games unless the conditions they wanted were met. Players could really only negotiate a new contract to play for another year with the same team, or ask to be traded or released. At the time, the players didn’t really have the freedom to change teams like they do nowadays unless they were released, traded, sold or released.

This lockout only lasted through March 1st to March 17th and did not affect any regular season games but did affect Spring Training. But it did introduce the concept of free agency, and abolished the reserve clause forever.

Then four years later, another strike incurred from April 1st to April 8th 1980, this caused the final 8 days of the spring training to be cancelled. It did not affect the regular season in anyway. CBA negotiations led to this strike, with both sides agreeing to an extent on the new CBA but both agreed that they would need to revisit ‘free agency’ in the following offseason. This brief lockout paved the way for one of the longest labor stoppages in MLB history.

The 1981 strike was long, ugly and at the time was the longest MLB strike to date. This strike lasted from June 12th 1981, all the way to July 31st 1981, with players returning for the All-Star Game and quickly resuming the season the day after. In total, the lockout cancelled 712 games and forced the season to be split into two halves.

A fifty day strike finally ended after both sides agreed on the matters of free-agent compensation. More specifically how teams that lose free agents are recompensed. At the end of the day, teams who lost free agents were compensated with some combination of unprotected professional players chosen from a league-wide pool as well as draft picks. Owners had initially insisted upon a compensation structure that would supple the team losing said free agents with draft picks from the signing team and players chosen from the roster of the signing team. The MLBPA saw that as an unacceptable drag on the free-agent market.

In 1985, the league had a very brief strike, which the common fan who doesn’t follow everyday probably wouldn’t have even noticed. This strike lasted only 2 days, through August 6th-August 7th. The MLB strike only lasting two days, proved that in-season labor stoppages don’t need to be detrimental to fans, owners, or players. But this minor strike, laid the foundation for something even bigger.

The 1990 lockout lasted from February 15th from March 18th, 1990. Spring training opened up late and ultimately pushed back Opening Day by a week. The disagreements started over free agency and salary arbitration with owners saying that arbitrators judgement were against them for rigging the free-agent market.

During the 90’ lockout, MLB commissioner at the time, Fay Vincent held a press conference. He proposed ending the lockout in exchange for a “no strike” pledge from the union. The only problem with that was that Vincent made that offer without consulting any of MLB’s owners. He was later then replaced by Bud Selig.

Selig who was an owner himself, saw the MLB out of the lockout who fully converted the commissioner’s primary role into serving the interests of team owners. Bud Selig is famously known for introducing the wild card, interleague play, organizing the World Baseball Classic and also introduced revenue sharing to MLB’s teams.

He is also credited with the financial turnaround of baseball during his tenure of MLB Commissioner with a 400 percent increase in revenue for the league and annual record breaking attendance.

The 1994-1995 strike was historical for multiple reasons, and unfortunately mostly all for the wrong reasons. The MLB strike lasted from Aug.12th, 1994 – March 31st, 1995, a 232-day strike. Sit back, get comfortable, let me tell you all about the longest MLB strike in the leagues history.

The 1994 season began without a labor agreement in place, but owners were persistent upon adding a salary cap. That led the players to strike late into the 1994 season. This strike very quickly showed off that it was going to get ugly really quickly, and that statement proved true just a month into it. With Commissioner Bud Selig canceling the World Series. The first time a World Series champion hadn’t been crowned since 1904.

Things got ugly throughout the 232-day strike, multiple people were brought in to bring an end to this strike. Including, the owners lead negotiation resigning, bringing in a federal mediator which ultimately failed to bring the both sides together.

The owners implemented a salary cap, while the MLBPA declared all unsigned players to be free agents. Selig and his fellow owners tried to populate the MLB rosters with replacement players/scabs.

It finally was settled after a National Labor Relations Board complaint and injunction issued by future Supreme Court Justice, Sonia Sotomayor. This brought owners to force the end of the strike. In addition to losing the entire 1994, the fans and players also lost a combined 938 regular-season games across the 94’ and 95’ seasons.

Unfortunately, the labor stoppage hurt the game for years to come. But this 232-day long strike did pave the way for the MLB to not have players strike in over 20 years.

22 years later, the MLB suffered it’s ninth work stoppage in MLB history. It started on December 2nd, 12:01 AM ET after MLB owners voted unanimously to enact a lockout due to the expiration of the 2016 CBA agreement between the MLB and the MLBPA. The lockout ended on March 10th, 2022 lasting over 3 months. This didn’t affect the cancellation of any games in the regular season but it did force Opening Day to be played, a week later from originally planned, as well as a shortened spring training.

Following over three months of on-and-off negotiations, the cancellation of the first two-series of the regular season. The MLB and MLBPA finally sat down and following a week of daily negotiations, the MLB and MLBPA reached an agreement on a five-year CBA on March 10th. The new CBA salvaged the full 162-game season and the two cancelled series were later made up in the season.

The lockout was officially lifted at 7:00 PM ET on March, 10th, restoring teams ability to be in contact with players and re-opening free agency. Which at the team was headlined by names like Carlos Correa, Freddie Freeman and Clayton Kershaw. This lockout, was also the first modern-day lockout with the age of the internet. Following the end of the lockout, the likeness of players was reinstated on official MLB websites. While MLB’s social media pages were finally able to stop only posting content about retired players, minor leaguers and miscellaneous topics.

The 99-day lockout brought in new additions to the CBA, including the increase of minimum salaries for the next four seasons, a pre-arbitration bonus pool for young players, a wider Draft lottery, and changes to service time rules to address the service time manipulation.

Other features of the CBA included changes to the draft, including guaranteeing a percentage of the pick value to top-300 prospects, the universal DH rule, raising the competitive balance tax and including limits on options to the minor leagues.

But now we are in present time MLB, and the game has changed a whole lot more since the last time the last CBA was negotiated. Super teams have now become the new normal for MLB, with the Dodgers, Mets, Yankees, Phillies and Blue Jays payroll all combining for over 1.50bn USD, that is over 500m more then the bottom 10 teams combined.

To explain this simply, this CBA negotiation will be mainly about money, it always has and it always will be. More specifically, it’s about how the sport revenues is divided among players and the possible implementation of a salary cap.

From MLB’s view, there are two paths to fix team spending at the top. First off, is putting limits with how high payroll can go, and two, taking money away from those big spending teams.

Now the MLB already has the luxury tax in place, but it seems to be ‘irrelevant’ to these bigger market teams, especially the Dodgers.

MLB team owners haven’t been quiet either about their wishes about a salary cap in baseball. Orioles owner David Rubinstein recently said this to R.J. Anderson from CBS Sports

“I wish it would be the case that we would have a salary cap in baseball the way other sports do, and maybe eventually we will, but we don’t have that now. I suspect we’ll probably have something closer to what the NFL and NBA have, but there’s no guarantee of that.”

Now limiting teams to a salary cap takes away the labor cost and at the end of the day, appeals to owners. This will force owners and GM’s to spend less money, in order to meet a certain set cap.

Some owners mention that being part of a capped league is better than the current alternative. This obviously appeals to owners who sees their funds given to them by semi-civic trusts (organizations or initiatives that bridge the gap between traditional civic engagement and private entities, often focusing on public interest technologies or community well-being.)

Implementing a salary cap is easier said then done though, we’ve been through this process before. More specifically in 1994, which led to the cancellation of the World Series. The MLBPA has never showed any type of willingness in agreeing to a salary cap.

Agreeing to a said salary cap, would also force teams to share their revenues with the players. Owners will one-hundred percent argue against this, saying that the stadium-adjacent real estate, and the equity states in sports networks aren’t baseball revenues. While the MLBPA will certainly argue that those money sources wouldn’t exist without the players.

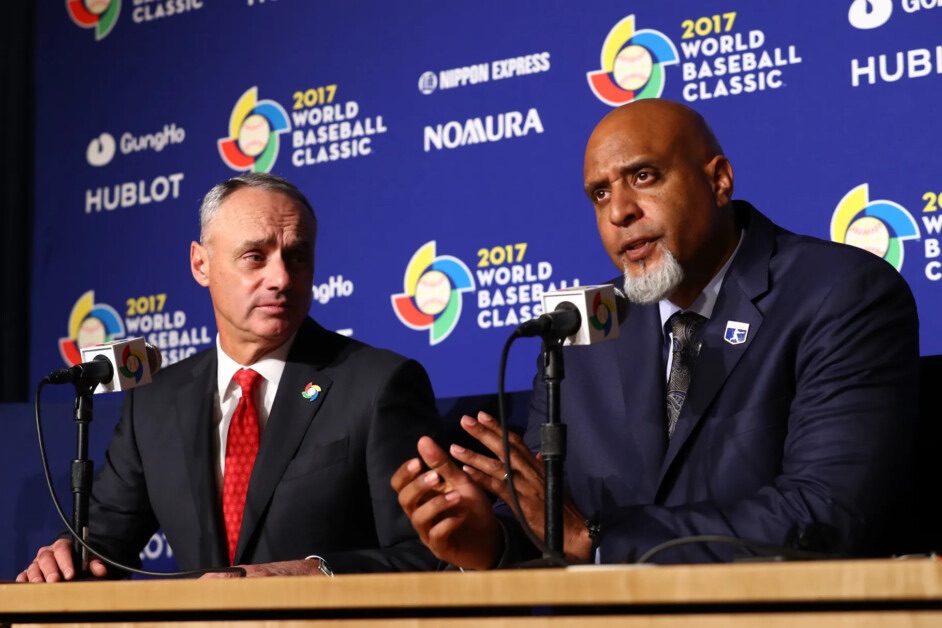

Rob Manfred, MLB Commisioner, recently hinted at the multiple different opinions he’s been hearing about the CBA talks.

“I have owners with really strongly held views that I need to coalesce into a position that we’ll ultimately take to the MLBPA.”

The tensions between the small-market and large-market team owners on the topic of revenue sharing is at an all time high. Revenue sharing could potentially mean taking money away from those big spending teams, in an effort to reduce labor cost.

Other issues that may be brought up during negotiations are owners trying to push for an international draft, and also asking the players to expand another round of playoff expansion – from 12 teams to 14

Now you may be asking yourself, will this CBA negotiation see the same light that the 1994 one did? Well, Commisioner Rob Manfred is preparing for an owner-led labor stoppage.

Here’s what Manfred said after being asked about the possibility of a lockout following the 2026 season

“In a bizarre way, it’s actually a positive. There is leverage associated with an offseason lockout and the process of collective bargaining under the NLRA works based on leverage that exists gets applied between the bargaining parties.”

After Manfred’s comments, Tony Clark, the MLBPA’s executive director said in February of 2025

“Unless I am mistaken the league has come out and said there’s going to be a work stoppage. I don’t think I’m speaking out of school in that regard.”

Despite the CBA being over 500 days away from expiration, Manfred’s comments solidified what we mentioned earlier in the year. A labor stoppage is coming to the MLB whether you like it or not. While there is more then enough time for things to change, the way i see it, we should 100% brace for a labor stoppage in 2026, and the potential stoppage of free agency signings.

Leave a comment